“I now urge the Legislature to pass promptly a legislative redistricting bill which will obey the mandates of the state and federal constitutions, provide equitable representation for all areas of the state and ensure that the party which wins a majority of the votes will win a majority of the seats in the Legislature.”

— Governor Dan Evans,

1964 Inaugural Address

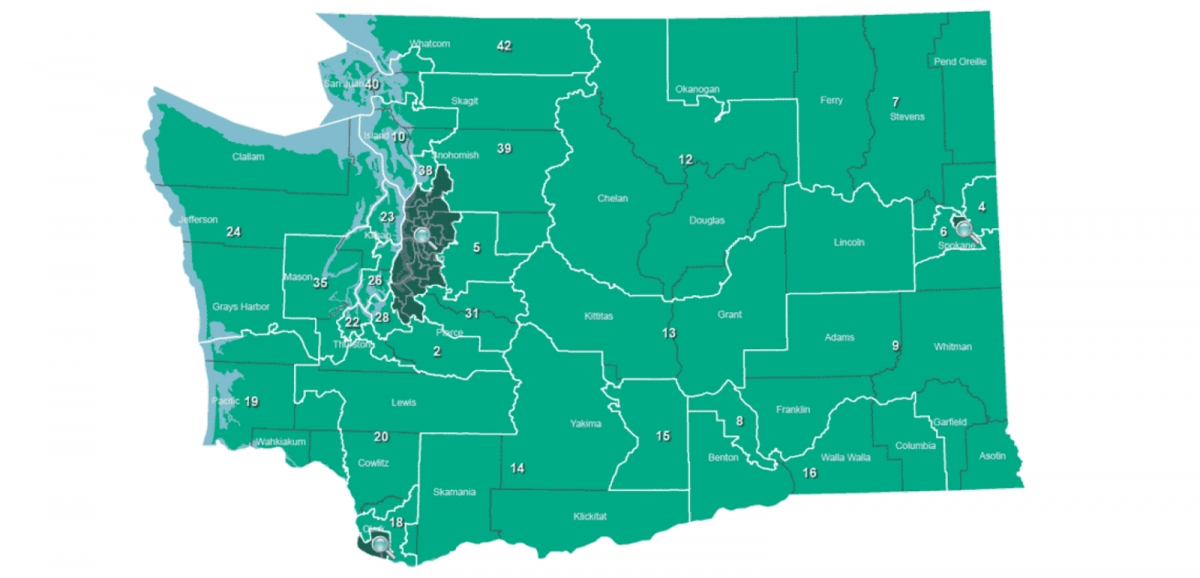

In the last week, our team at the Wire posted a series of stories about Washington State redistricting, its history, legal framework and some insights from some of the players engaged in the once-a-decade discussion.

It’s not a sexy topic. And, there aren’t a lot of folks talking about this today, in 2019. But, maybe they should be.

Maybe this year, before attention begins to focus on how the state draws the lines, there can be a few subtle changes that would strengthen this process for the next generation.

It’s a framework that hasn’t really been updated since 1983. Perhaps Washington State has changed enough that it’s time to modernize how we draw the lines here.

The Morning Wire: Keeping you informed on politics, policies, and personalities of Washington State.

Here are 5 things that have stood out to me as we’ve worked through this research that underpins why it’s time to consider an update to our model.

1.By at least one measure, Washington State draws districts with as much benefit for Republicans as does Texas.

For her story, Sara Gentzler researched a wide range of states to review the results from the 2018 midterm elections. Texas is often regarded as a state with a legislative map drawn to favor Republicans heavily. In what was considered a “blue wave” election, the result of Texas’s redistricting was that Democrats were only able to move their state House representation to equal the 2016 statewide performance. In other words, after a “wave” election, the map was drawn in such a way as to limit Democrats’ voice in the House to only equal the 2016 benchmark.

Notably, the same thing happened in Washington State: Democrats only moved from under-represented to equal to the 2016 benchmark. From Gentzler’s story:

Democrats in the Washington State House went from under-represented by 7 points to evenly represented compared to their statewide presidential votes…

The House in Texas approached voter preference in 2018 similarly, albeit from the other direction. In recent presidential elections, 56 percent of Texas voters have voted Republican, while 63 percent of the state’s House was red. Post-2018 midterms, the Texas House is 55 percent Republican — just about even with the statewide preference.

While Texas is often regarded for a legislative map that is gerrymandered in favor of Republicans, Washington State is not. Yet, following the “blue wave” election of 2018, both states’ Houses of Representatives moved from over-weighted toward Republicans to a partisan split that evenly matched the statewide vote.

In other words, Washington State’s map favors one party just as much as Texas’s map does.

2. Washington defines ‘no partisan’ advantage by custom, not law, in such a way that explicitly creates partisan advantage

As noted in item one, the Washington State redistricting model tilts the playing field towards Republicans. In Marjie High’s story, she reviewed the statutory and constitutional legal foundation for Washington State’s re-districting model. That included a build up to the 1983 state constitutional amendment that is still the operative model for the state.

It’s in the space between the intention of the 1983 law and the reality of elections in 2019 where the advantage forms. From High’s article where she highlights the direction provided to the redistricting commission:

Codified at RCW 44.05 et. seq., RCW 44.05.090 provides that the commission should “exercise its powers to provide fair and effective representation” and that “the commission’s plan shall not be drawn purposely for favor or discriminate against any political party or group.”

It was this language providing no partisan advantage that helped to build and hold bi-partisan support for the model since passage in 1983 – and which has earned Washington State high praise from observers across the country.

Because the statute and constitution are so clear that district boundaries cannot “favor or discriminate” one party, and because the commission must have representatives from three of the four caucuses agree to the map, what results is a map that is essentially a 50-50 map, one giving equal weight to both parties.

Is it any surprise then that the Washington State legislature has been practically deadlocked at an evenly split legislature for a fair portion of the last decade, despite statewide Democratic performance ranging from 56-58%, depending on how one counts that benchmark?

One could argue it’s because of the maps.

3. The ceiling and the floor matter, or put differently, the number of truly swing districts is important

In our review of the 1965 and 2012 redistricting efforts, we get a window into at least two strategic approaches to drawing maps.

One approach employed by Slade Gorton in both years was to maximize the number of swing districts. The idea was to give Republicans as good of a chance as possible to put together a majority in any given year.

Another approach may have been to limit the possible variation in election outcomes. This may have been the approach taken by House Democrats in 2012, which may have had the consequence of limiting the potential number of new Democratic members in exchange for a more reliable “floor” for Democrats. The statistical data shows this worked, if that was the strategy.

So, within the sideboards of “one person, one vote,” it’s clear there is a range of ways to draw maps. Just as in a state like Texas, this means that the kind of representation in Washington State’s House of Representatives is significantly impacted by strategic considerations made at the start of the decade when lines were drawn.

4. If the legislature is going to modernize the 1983 redistricting process, 2019 is the year to do it

If the legislature were to modernize the way Washington State draws its maps, this would be the year to do it. The 2020 general election will be a partisan and contentious one. The 2021 session will not have enough distance from the 2020 general election for a proper discussion on the matter, one that should be as removed from political considerations as possible.

Moreover, because of the current model that tilts the legislature towards an arbitrary 50-50 split, under-weighting the Democratic performance in the state, it’s likely the legislature will revert to an even narrower majority in 2023.

In other words, now is the time to review this matter.

And, there may not be too much time to wait. A number of states have had lawsuits brought by organizations, citizens or advocacy groups that sought to change the way lines are drawn. As the difference grows between the Democratic vote in Washington State – the state with the longest single party control of the governor’s mansion of any state in the Union – and the Democratic representation in the legislature as a result of redistricting, one could increasingly reasonably argue that the courts should step in.

Put differently, this seems like the kind of thing that progressive interest groups might want to litigate before the next census if the legislature doesn’t otherwise act.

5. Here are two things the legislature could consider to modernize the way we draw lines

First, creating an arbitrary (and capricious?) benchmark like a 50-50 split for maps seems as antithetical to drawing maps that are not discriminatory as would be creating a benchmark of 100-0%. Neither has any basis in law.

Moreover, the extent to which the statewide partisan performance varies significantly from a 50-50% split is the extent to which one party or another will suffer.

One way to address this is to clarify the policy, something expressly given to the legislature by the state constitution. In section 43, the constitution reads,

“The commission’s plan shall not be drawn purposely to favor or discriminate against any political party or group.”

In RCW 44.05.090(5), the statute reads:

“The commission shall exercise its powers to provide fair and effective representation and to encourage electoral competition. The commission’s plan shall not be drawn purposely to favor or discriminate against any political party or group.”

However, neither document defines what “not be drawn purposely to favor or discriminate” means.

Here is where the legislature should focus its efforts. Instead of a law that directs against a negative action, it should draft a law that directs for an affirmative action. The legislature can define what it wants to see here. That might include:

“Drawing maps to not purposely favor or discriminate against any political party or group means to draw maps that reflect the statewide partisan performance from the general elections in even years over the course of the last ten years, to include an aggregate of the results of all statewide executive offices, presidential elections, and US senate races.”

That is similar to the logic we’ve used in this series. But, it could be any other logic that is reasonably construed to reflect the will of the electorate.

Secondly, the legislature could define “encourage electoral competition” by directing that some number of districts are drawn to be swing districts.

An interesting by-product of a larger number of swing districts, to Sen. Gorton’s point, is that it will make the remaining districts more partisan. And, as we saw in races like the 32nd senate race this year, that might generate more interest in active primaries. Primaries are less attractive to parties concerned about losing seats to the other party. More single party seats – a result of more swing districts, to Gorton’s point – would potentially create more competitive districts under our current top-two primary model.

In other words, “encouraging electoral competition” could come in multiple ways, but it should come as a result of a legislative policy. It shouldn’t be as a result of voter initiative or court intervention, which is the legacy of redistricting in Washington State before 1983.

Bottom line: redistricting Washington State has a recent history of bi-partisanship. That belies a much more contentious history of citizen initiatives, court cases and political gamesmanship in Olympia prior to 1983. By taking for granted the bipartisan nature of our current model, natural changes in demographics, along with strategic political considerations, have allowed the partisan advantage in Washington State districts to match, by one measure, the partisan gerrymandering of states like Texas.

Before this issue goes back to the courts, and before the politics of 2020 crowd out a window for a bipartisan approach, the legislature might want to consider clarifying the policy embedded in the model for how we draw the lines in Washington State.

Your support matters.

Public service journalism is important today as ever. If you get something from our coverage, please consider making a donation to support our work. Thanks for reading our stuff.