During our interview with Slade Gorton, and in his biography by John C. Hughes, Gorton said that one of his goals in the 1965 redistricting was to maximize the number of swing districts on the map. From Hughes’s biography:

“The goal was to create enough strategically placed Republican swing districts to give the party a fighting chance in lean years and a majority in good ones. No mean feat. One squiggly line bisecting a neighborhood could spell defeat or victory.” (p. 54)

Obviously, this can be done within legal sideboards, adhering to the “one person, one vote” principal established by the courts. Democrats tried to find their own partisan advantage in 1965, however, that year Gorton was the victor over his partisan opponent, Democratic Senate Majority Leader Bob Grieve.

The creation of enough Republican swing districts led to Republicans holding the House majority for six years — from 1966 to 1972 — when the districts were redrawn.

The Morning Wire: Keeping you informed on politics, policies, and personalities of Washington State.

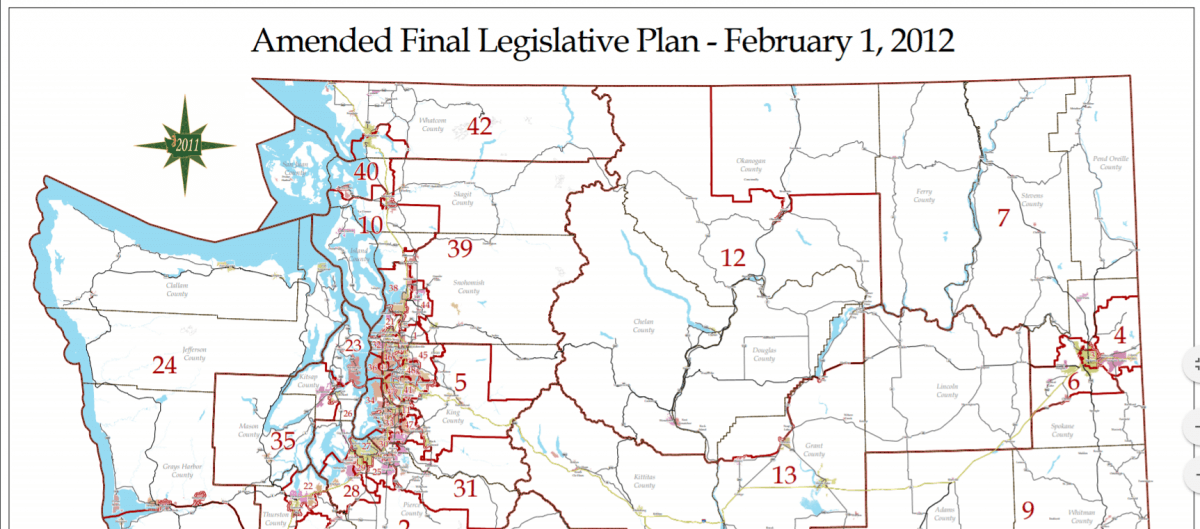

In the 2012 redistricting process, things got a bit more complicated.

In our podcast conversation with Gorton, he discussed the challenge of building a map that adequately reflected the statewide trend.

“The more swing districts you create, the more single party districts you create…

In Seattle, the districts are 80-85% Democratic. In Eastern Washington, the districts are 60-65% Republican… Candidates make a great deal of difference. It isn’t all mathematics by any means. It has to do with candidates.

If one wanted to create swing districts that Republicans could win, stocking up Seattle districts with Democrats is one way to do that. This is particularly the case in a state with a Democratic performance of 56-57%.

But, that wasn’t the only consideration in play in 2012.

Over the last few months, in addition to Gorton, I spoke with a handful of individuals close to the redistricting process in 2010-2012, and who were involved to some degree in conversations related to redistricting strategy from the view of the House Democrats. All of them spoke on condition of anonymity because of Frank Chopp’s leadership role in 2010 and continued leadership in 2019.

Pieced together, their stories suggested that House Democratic leadership was interested in narrowing the number of swing districts in 2012. This strategy sought to have the Democratic “floor” come up, meaning it was less likely that Democrats would lose the majority. At the same time, the Democratic “ceiling” (otherwise known as the Republican “floor”) would come down as well. From the view of the House Democratic leadership at the time, the idea was to limit the number of members in the House Democratic caucus to a “majority that was more manageable” than had been the case over the previous decade.

In the 2000s, the House Democratic Caucus averaged 56.8 members, or 58.0% of the chamber, exceeding the average statewide Democratic vote of 53.6%.

The size of the caucus last decade meant a larger – and in some cases more unwieldly – Democratic bloc. The caucus included a large moderate group with members like Deb Eddy. It also included a vocal labor component with members like Geoff Simpson and Mike Cooper.

At one point, a “Blue-Green Caucus” was formed that tried to redirect the House agenda towards issues Democratic leadership didn’t want to address.

From a story by Austin Jenkins in 2010:

“…the so-called Blue-Green caucus, a reference to more than a dozen labor-and-environmental-minded House Democrats who have come together to stand as a bulwark against the, at times, centrist tilt of the House caucus. This view is at odds with the more conservative House Democratic leadership as personified by House Majority Leader Lynn Kessler of Hoquiam. Last year, the Blue-Greeners flexed their muscle at the end of session. This year… there’s the potential for more intra-caucus fireworks over the budget.”

The point of this example, I’m told, is that Chopp was willing to deal away a larger majority in the last redistricting effort for a more stable one. From one observer’s point of view:

“When you have a narrower majority, everyone in the caucus has to be on the same team otherwise nothing moves and the whole team suffers. That really strengthens the hand of leadership who can say there aren’t the votes to freelance on issues or cobble together votes outside of the caucus.”

If we take an empirical look at the partisan composition of the Washington State House of Representatives during these two periods – 2002-2011 and 2012-2019 – and the shifting statewide Democratic performance over this time, they would appear to be moving in opposite directions.

In other words, while one can’t know what was in the heads of House leadership in 2010-2012, one can look at the data to see if it supports the notion of a reduced Democratic majority.

And, the data suggests a significant shift took place in the 2012 redistricting, reducing the size of the Democratic majority.

In 1965, the prevailing notion was to maximize the swing districts so that Republicans could have a more-than-reasonable chance of holding the majority.

In 2012, it may have been the case that opposite interests prevailed: that a narrowing of swing districts elevated the House Democratic caucus floor while also reducing the likelihood there would be a large Democratic majority.

If you’re trying to lead a diverse group of left of center legislators, this might have been the best way to do it.

Your support matters.

Public service journalism is important today as ever. If you get something from our coverage, please consider making a donation to support our work. Thanks for reading our stuff.