The original Evergreen Point Bridge cost $159 million to build, in today’s dollars. The replacement will cost $4 billion more.

OLYMPIA, March 5.—Last week’s revelation of big problems at the 520 floating bridge project in Seattle couldn’t have come at a better time for critics of this year’s transportation proposal. Republicans say those cracked bridge-floaters are just the tip of the pontoon, and they want big changes at the state Department of Transportation before they’ll support a dime in new taxes.

Whether the spate of nasty headlines about DOT projects really has anything to do with their reluctance to embrace a big tax increase is a different matter – the $10 billion proposal floated by House Democrats two weeks ago is proving difficult for many lawmakers to swallow. But the furor at the statehouse does call attention to one of the strangest and perhaps most alarming facts about the state’s road construction projects. For some reason, asphalt is a whole lot more expensive than it used to be.

Consider: The original Evergreen Point Bridge across Lake Washington, the world’s longest floating bridge, cost $21 million when the state allocated money in 1961. That’s $159 million in today’s dollars. The replacement project is expected to cost just a tad bit more – somewhere between $4.1 billion and $4.6 billion. Certainly the new project is a little grander than the old one – there will be an extra lane in each direction, it will be better designed to withstand earthquakes, there will be a lidded park near the I-5 interchange. An entire museum had to be moved out of the way. And there are new goodies to satisfy seemingly every interest in Seattle with an open palm. But a $4 billion difference?

That’s what House and Senate Republicans are harping about when they talk about reform, says state Rep. Ed Orcutt, R-Kalama, the House Republican transportation lead. “Consistently we are higher on similar projects that every other state in the nation,” he says. “If we were doing things right, sometimes we would be higher, sometimes somebody else would be higher. But we are higher every time. It is a problem that needs to be fixed, and if we just give them more money now and we don’t get the fixes, it is not going to be fixed.”

Republicans this week say they will roll out a spate of transportation-reform proposals; certainly their insistence has implications for the chances of this year’s transportation package. And it does appear that Inslee’s new pick for transportation secretary, Lynn Peterson, can expect a grilling when she comes before the Senate for confirmation. But the whole affair does seem to have forwarded a new question to the center of the table: How come road projects cost so much?

Splendid Timing

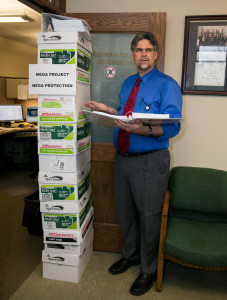

“Mega Project, Nega Protection”: State Rep. Ed Orcutt, R-Kalama, stands alongside the eight boxes of documents he got from the Department of Transportation when he requested information about the 520 pontoon problem.

Last week’s news about the bridge offered an astounding bit of timing. Less than one week before, House Democrats and transportation interests had rolled out one of those transportation-financing efforts that come every few years. The 10-year, 10 billion package seemingly has something for everyone – for the state’s big “mega-projects,” local governments, transit interests and environmental groups. Money would come from an eventual 10-cent increase in the gas tax, long-term bonding for short-term projects, and a resumption of the car-tab tax Washington voters have rejected twice at the polls. Critics immediately began talking about reforms before revenue, and it might have sounded like a matter of political mantra until the news about the 520 bridge was made public.

To save money, the state elected to design 33 concrete bridge pontoons itself, which will eventually be cemented together to form a 1.5-mile barge across Lake Washington. The winning bid was $367 million, some $180 million less than the state otherwise expected to pay. But when the first pontoons were cast and hauled to Lake Washington, divers discovered big cracks. Repairs might run as high as $100 million. Because the state itself is to blame for the design, there’s no one it can sue.

So now the state is demanding answers and looking to assign blame. Gov. Jay Inslee is saying someone will take the hit: “I have charged my secretary to get to the bottom of that, and there will be letters that will be going out shortly to some Department of Transportation employees basically telling them that their conduct will be reviewed and that appropriate discipline will be decided after their due process rights are respected.”

At a news conference last week, Republican leaders in the state House and Senate said the bridge trouble is the latest in a disturbing pattern of management blunders at the Department of Transportation. “Until Washington state can have some sort of confidence around DOT’s ability to do the project correctly, I don’t think we can continue throwing good money after bad,” said House Minority Leader Richard DeBolt, R-Chehalis.

Spate of Nasty Headlines

The Department of Transportation has found itself on the hot seat quite a bit in recent years – about costly change orders on the Alaskan Way Viaduct replacement project in Seattle, high-cost construction for new state ferries. There was apparent failure of the bi-state planning agency responsible for the Columbia River Crossing at Vancouver to communicate with river users in the Portland area about the needed clearance for the new bridge – forcing designers to go back to square one after years of planning. There was also the million-dollar goof in Tacoma, in which a new off-ramp from Highway 16 had to be partially demolished because the project needed three lanes, not two. They’re the kind of stories that have become staples of Seattle TV newscasts, and for the most part the agency has well-practiced answers for complaints about its management processes. In most cases, the state awards design-build contracts that make contractors liable for design problems, said chief of staff Jeff Reinmuth. 520 was different; the state was looking to save money and time. “I can assure you no one at the department will ever recommend that we take the design within a design-build project again,” he said.

Of the 421 projects funded by the last rounds of gas-tax increases, in 2003 and 2005, 400 have been completed, 80 percent were completed early or on time, and 91 percent were completed on or under budget, he said. The state auditor has suggested that some of ferry-construction costs can be blamed on a state law requiring construction be kept in-state, meaning only one bidder qualifies – but the law was the Legislature’s doing, not DOT’s. If you look at construction costs for the latest ferries as a class – not just the problems on the first boat, the Chetzemoka – Reinmuth says the state brought in the project for $6.7 million under budget. Yet the systemic issues – the ones that have driven up costs dramatically since the golden age of freeway-building – are a little harder to explain. So how come it costs an extra $4 billion to build a bridge?

There are communities that have to be satisfied, Reinmuth says, and they all want some form of “mitigation” – traffic improvements, noise reduction, bike paths, pedestrian walkways. Environmental permits must be obtained, meaning designs must accommodate environmental concerns. “We take that stewardship and responsibility very seriously, and it is not inexpensive. When you look at the amount of engineering, the amount of construction, the amount of environmental work and the amount of community mitigation that needs to happen, it all adds up. And with all of the hundreds of public hearings that have happened on the 520, and with all of the concerns that have been addressed and built into the design, all those things add to the cost of the bridge.”

Like the ‘Big Dig’

Being sensitive to all humanity certainly carries a cost, but there are other factors, like a state policy that in some cases requires sales tax to be paid on the cost of an entire project. That boosts costs by about 8.5 percent, essentially shunting gas-tax money into the general-fund budget. State and federal prevailing-wage requirements, set by state surveys that don’t reflect market conditions, add perhaps 10 percent to project costs.

The big costs on the 520 bridge project offer a perfect illustration of the end result, said Michael Ennis of the Association of Washington Business, at a hearing of the House Transportation Committee Feb. 18. Two bridges across the same span of water, one costing $4 billion more. You have to separate natural cost drivers like inflation and ordinary economic forces from the effect of government policy, Ennis said. “I’m not here to argue the validity of these policies,” he said. “I would just encourage you to recognize the distinction between these natural and unnatural cost drivers. The decisions that we make can inflate the costs artificially of these transportation projects.”

So how does Washington stack up? Transportation consultant Bill Eager, president of TDA Inc., described an analysis he performed under contract for Bellevue’s Kemper Development Co. He looked at costs at 130 road projects in 26 states and 15 countries and came to a startling conclusion. When similar projects are compared, Washington’s always is the more expensive. In the case of the tunnel that is being dug to replace the Alaskan Way Viaduct in downtown Seattle, costs are about $230 million per lane mile. “It puts us almost in the same range as Boston’s ‘Big Dig,’ and it is about double the average for three U.S. central-city projects,” he said. “The same is true for 520 from I-5 to Medina – that is about $115 per lane mile, about double for 14 U.S. bridge projects.”

Eager cautioned that every road project is different, and there might be mitigating factors. “I am sure that DOT would say this is risky because each project is unique, and I would have to agree with that,” he said. “We can’t pick 405 and go somewhere else in the U.S. and find a project that is just exactly like it. The thing that was striking to us, however, was that in looking at this large number of projects, there was a pattern, and the pattern was that with few exceptions, DOT always came out on top, at the highest end of the cost.”

One other finding: The nearer the project got to the Space Needle, the more expensive it was. Seattle interests in particular appear to demand that transportation projects pay the price for problems they don’t create, he said, and that seems to be one of the big cost drivers. Eager called for the state auditor to conduct a broader analysis to determine what is driving up costs.

Reform Proposals Afoot

The Associated General Contractors have suggested a raft of reforms, among them streamlined environmental permitting processes and incentives for private investment in projects of statewide significance. The state ought to review its environmental regs to see if too much acreage is being set aside for stormwater runoff collection and sedimentation ponds, said AGC lobbyist Duke Schaub. And other changes to construction practices, including development of highway detour routes and weekend closures, might also reduce costs. “With the increasing need to maintain what we have with declining revenues, there are many examples from other states and European countries that could be applied to Washington state to reduce costs,” he said.

Orcutt said the reform proposal due shortly from House Republicans will include a proposal to exempt future construction from sales tax. Other measures that are part of the package include traditional Republican priorities, like requiring state permitting decisions in 90 days and suspending growth-management act requirements in areas with high and persistent unemployment. Transportation reform is a fertile field, he says. “What we are trying to do with the bills that we are trying to develop right now is to give the citizens what they deserve, and that is projects at a reasonable price. We want to make sure that tax dollars go further before we go further into taxpayers’ pockets.”

Your support matters.

Public service journalism is important today as ever. If you get something from our coverage, please consider making a donation to support our work. Thanks for reading our stuff.